Behind the Art: The Real-Life Refugee Stories That Inspired New Uptown Mural

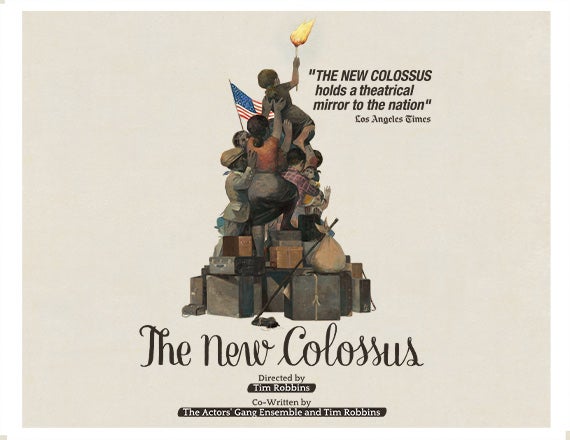

The national tour of THE NEW COLOSSUS kicked off in Charlotte this week, and a brand new mural outside of Knight Theater has been created to mark the occasion. The play, directed by Tim Robbins, shares the real-life stories of 12 refugees spanning different eras and fleeing different countries around the world in search of a better future in America. Each actor portrays one of his or her own ancestors in a production that shows how individual stories of courage, resilience and dignity are woven into the fabric of our shared history as a nation.

Charlotte-based visual artist MyLoan Dinh, once a refugee herself, also explores the connections between the personal and communal in her artwork. The new mural features a reproduction of her piece, “Collective History.” The original mixed media creation is also currently on display in the Knight Theater lobby (courtesy of Elder Gallery of Contemporary Art) and is layered in meaning, with elements representing Dinh’s own family’s experience fleeing Vietnam, as well as references to the communal experience of refugees throughout history and in contemporary times.

Dinh says her work has always referenced her cultural identity but it used to be more subtle. In 2016, that changed. She was in Berlin working on various projects, when the issue of Syrian refugees and what to do about this “problem” came to the forefront. (Dinh and husband Till Schmidt Rimpler—founder of the multi-disciplinary arts group Moving Poets—split their time between Charlotte and the German capital. More about that later…).

People were asking, what should Europe do? Who is responsible for these refugees? Who should take them in? And were they going to change the culture of Europe?

“There was a lot of fear from people,” says Dinh. That hit her hard because it made her think of her own experience as a refugee.

Across the ocean, incidentally, Robbins and the Actors’ Gang ensemble were also deeply affected by the Syrian refugee situation. That’s what planted the seeds for what would become THE NEW COLOSSUS.

(MyLoan Dinh with The New Colossus co-writer/director Tim Robbins)

“The question is, as an artist, what do you do when you’re confronted by things that bother you to the core?” asks Dinh.

“You make art… Because I’m able to process this information through my artwork and share it with others, it helps me to cope.”

“Collective History” measures approximately 5.5 ft by 4 ft. The original piece is created on canvas and incorporates old quilts, hand embroidery, paint, paper and other materials. Here’s a look at some of the symbols Dinh uses in the piece to explore the refugee experience and the stories behind them.

SOME OF THE IMAGES YOU’LL SEE IN “COLLECTIVE HISTORY”

A LITTLE GIRL is featured prominently at the bottom left of the painting. In part, she represents Dinh, who was only three years old when her family fled Vietnam in 1975, during the fall of Saigon. The family was aboard the very last naval ship to leave. Dinh’s father had been part of the South Vietnamese navy, fighting alongside the Americans, and knew the Viet Cong would soon be arriving.

He hadn’t planned on leaving, however, because he had an ailing, elderly mother with whom he was very close. But when he reported to work at the naval office on April 29, personnel were shredding papers and he was instructed to destroy his uniform and all official documents bearing his name.

“From one day to the next, he wiped out everything that showed what his history was,” says Dinh. Not doing so or staying in Vietnam ultimately would have meant being sent to a reeducation camp for forced labor, indoctrination, and potentially worse.

The little girl in the painting is also meant to represent other refugee children. Dinh recreated the image from a newspaper photo of a mother and her two children, part of the much politicized migrant caravan in 2018, being tear gassed at the US/Mexico border.

You can see the full image behind a screen on the bottom half of the artwork. Dinh encourages viewers to use the flashlight mode of their cell phone to illuminate the screen if they can’t see all of the details.

“Like a lot of things, what you first see is not the whole story,” she says. “Look further, and deeper to see more of the picture. That goes for history, what’s going on politically, socially, all of that.”

Another element of the work are the TWO PAPER BOATS, at which the little girl is gazing. This is a reference to the Dinh family’s experience leaving Vietnam. They left on an old boat, designed to carry about 50 people and military equipment but instead was crammed with about 1,000 desperate people. The only reason the ship was available to them, Dinh says, was because the engine wasn’t fully functional.

Then the ship began to sink.

Luckily, they weren’t the only group out there and another refugee ship came to rescue them. In the midst of the ocean, there were tens of thousands of refugees with no place to go. Dinh says the US Congress wasn’t willing to give any orders about what to do with them because the most important people—the Americans and soldiers—had already been evacuated.

“We were not special enough,” she says.

Ultimately, the commanders on a US naval ship, the USS Kirk disobeyed orders in order to prevent the refugees from perishing at sea. The Vietnamese flag was lowered on the Dinh’s ship and the American one raised, putting them under the default protection of the Americans. They were taken to refugee camps, first in the Philippines and later to Camp Pendleton in Southern California.

One of Dinh’s most poignant memories of the refugee camp was of her mother, spotting her own sister across a crowded canteen in California. Her aunt had left Vietnam several weeks before Dinh’s family. With no internet or cell phones, it was nearly impossible at that time to know if people had survived their escape. Miraculously, the two sisters had ended up in the same camp half-way across the world.

“I remember them embracing and crying, out of joy and relief,” says Dinh.

OLD DISCARDED QUILTS are also used throughout the artwork. “These are all hand made,” she says. “Somebody made them with love and intention.”

Created from bits and pieces, quilts also evoke quilting bees and community, says Dinh. They are things of beauty but then they are discarded… just like refugees. But we are also “a quilted nation of people coming together to create something beautiful and colorful together.”

In “Collective History,” quilting provides texture throughout the image. It’s used for the child’s clothing and behind the screen are also LITTLE HOUSES stitched into the quilts.

According to oral history, Dinh says, quilts were used in the underground railroad to relay coded messages, helping to guide runaway slaves safely from one place to another on their journey to freedom. In contemporary times, there have been reports of religious institutions bonding together to help refugees or undocumented families move from one home to another, in a sort of modern day equivalent of the underground railroad. “They knew this was against the law but they knew it was the right thing to do,” says Dinh.

THE HANDWRITTEN POEM in the piece features the words of Emma Lazarus. This well-known sonnet, permanently affixed inside the Statue of Liberty, also helped inspire the play, THE NEW COLOSSUS. In Dinh’s artwork, it is written by her own daughter, the child of two immigrants. Note also the envelope, which is completely COVERED IN EGGSHELLS, symbolizing the fragility of this letter of humanity and freedom.

A WORK IN PROGRESS

The power of art, says Dinh, is in the specific stories it can convey. “Whether it’s visual art, theater, music, dance, film… it’s visceral storytelling… we can see ourselves in that.”

Dinh says she hopes her artwork will spark interest in others to learn and think more about their own relationship to the themes of cultural identity, memory and displacement. “...[T]heir history is also in there. I think that once people realize that they are also a part of it then it’s harder to ignore.”

“Collective History,” is part of a larger, evolving multidisciplinary project founded by Dinh, called We See Heaven Upside Down. It has had four migrations—including gallery exhibitions and performances in Berlin and Charlotte, as well as community outreach components, involving 50+ artists to date.

It will culminate in HEAVEN (Feb. 27 - March1) at Booth Playhouse, a performance piece featuring actors, dancers, musicians, and live projection mapping. The story revolves around an immigrant girl separated from her parents, who goes into her imaginary world to survive. HEAVEN is presented by Moving Poets, whose mission includes bringing a community of artists of different cultures, age groups and disciplines together to create new works. For more info, go to https://movingpoets.org.